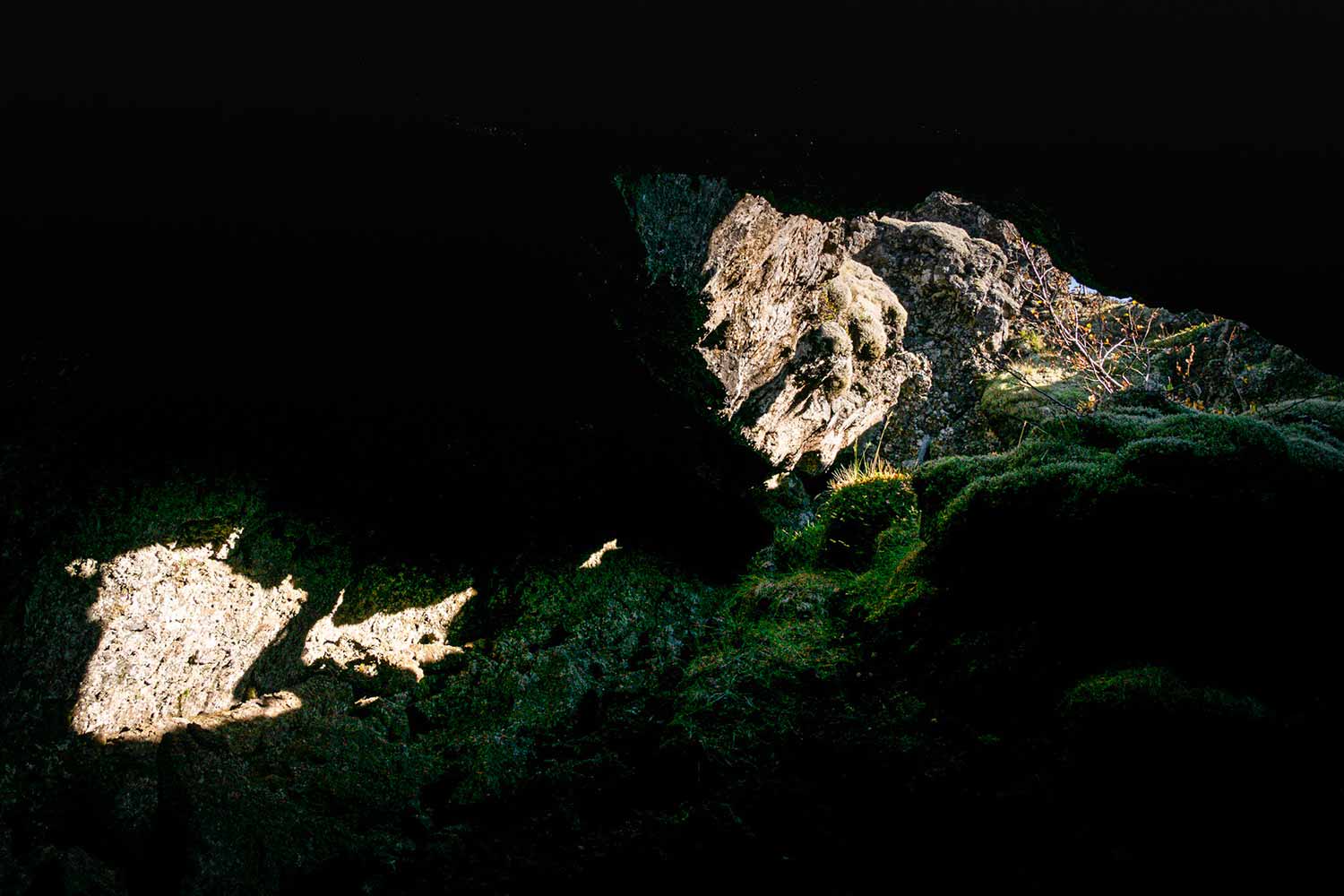

The sound of the wind echoes in my ears as I walk slowly along the coast. I am alone on the trail. No cars, no plane noises, no discussions. Only the sound of the waves, the wind, the screeching of my bag, my breathing and the chirping of some birds. I am alone since two days. I walk on Hornstrandir surrounded by loneliness. There is only me and my mind. Me and nature. Me and simplicity. I do not feel alone. I have always enjoyed loneliness. I can spend days without talking to anyone or feel the need for human contact. I think I would be able to be a hermit, perfectly at ease surrounded by no one.

The farmer on the dairy farm, where I worked for two weeks, continually talks asking me strange questions with an accusing tone. What is my opinion about Trump? Are my glasses dirty all the time like his? Why are women better at shopping than men? Am I aware that the French have their hands stained with the blood of colonized peoples? What is my opinion on the Icelandic dairy farm business? Why am I eating vegetables and not meat? I feel chained under the accusing eyes of a jury looking at me with bulging eyes of madness. I try to answer but answers do not interest him. Each question brings another. “The discussion only interests me if the other opposes me. Otherwise it does not matter”, he tells me. But how can you argue or make someone listen to reason if he only seems to flourish in conflict? This is not discussion. There are no interactions. Just a bombardment of platitudes learned via television or YouTube. My brain is saturating, I need silence, calm, loneliness.

Human contacts are always difficult. And after almost two months cycling and walking around Iceland, the vast majority of time alone, I find them even more difficult. Communication is never right, never exactly true. Our words never fully correspond to what our mind is trying to convey. Language always betrays our true intentions. Exchanges are difficult because they always involve judgment. We always see each other only through the vision of our own history, our mistakes, pains, successes. No matter what the other person says, his words will be analyzed anyway through the filter of our existence. While he tries to convey the truth of his intentions, our analysis is likely to interpret them in a different way.

The farmer accuses us, Anneli and I, to do nothing while a guest will come in the day. We should have known that we had to vacuum and clean the floors. It seemed obvious to him so he did not warn us. And now he is angry because the cleaning has not been done. Unconsciously, we always think that others see the world in the same way as we do, think like us and are therefore able to read our thoughts and understand us. But how is this possible when communication is based on judgment and limited vocabulary? Living with others implies, systematically, permanently, making compromises. You have to give up your freedom to set up a relationship. Every relationship is an attack on the freedom of the other. And all exchange involves tons of superficial speech.

On the other side, there is Sanni and Anneli. Both around forty years old. Finnish and Estonian. They are also present at the dairy farm. We exchange in English about our cultures and experiences. These are two people I do not know and yet I understand them perfectly. They see life in the same way as me: without alcohol, without drugs, without caffeine, oriented vegetarian, questioning the current changes in the world and environment, loving solitude and simplicity and centered on contact with nature, animals and travel. These young women come from cultures different from mine with their stories and problems and yet they seem so close to me, to my way of thinking. The nationality difference seems futile and I have the impression of understanding them better than many French people.

How can three people from different countries and cultures be so close? How can we understand each other? Are we, with the right circumstances, all able to be understood beyond language? Or am I able to understand them only because they have the same approach of life as me? Am I able to understand only people who are similar to me?

To speak several languages or at least to be interested in it seems to me to be a step towards the salvation of the understanding of the other. Each language has its own way of seeing the world and describing it. To be able to exchange in several languages or to mix them up, is to have within reach a vocabulary capable perhaps of putting words on our thoughts, these electrical events born of our brains. Get closer to the truth.

Spending two months surrounded largely by loneliness made me realize just how superficial and unnecessarily complicated our exchanges and interactions are. When traveling, when the only person to exchange is my bicycle, decision making is quick and easy. Eliminate the superfluous and get to the point. This is what attracts me more and more in solitude and in contact with nature. No endless speech, no judgments of the other, no betrayal of language, no compromise. Just simplicity.

Sanni told me one day, as she was telling me a story of a group of hikers with whom she was traveling in Alaska and who would gather in the evenings to smoke drugs and tell each other superficial stories, that she was feeling out of step with them and the only thing she wanted was “to go back to her cows, go back to something sensible”. It resonated in me. Live in contact with nature and animals, in simplicity, welcoming loneliness. There lies the truth.