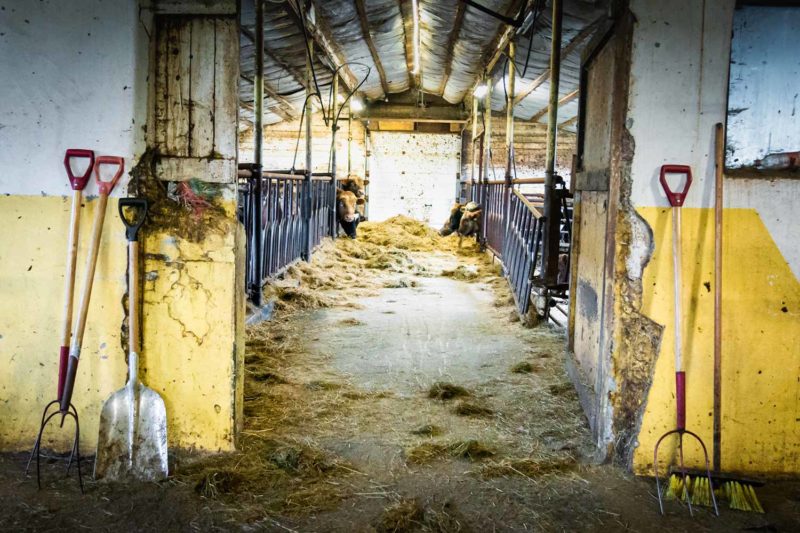

This morning, Cinderrella is not happy. She stomped, trampled and dropped the milking device I just put on her with difficulty. Sanni comes to my rescue. In a few quick and precise gestures, she calms the animal and puts the milker back in place. The milk flows quickly through the pipes accompanied by an automatic suction sound. And I go to the next cow.

Every morning and evening since a week, I participate in the milking process of about fifty cows on a small private dairy farm. For two weeks I decided to do an “helpX“, a voluntary exchange, to see another side of Iceland. Interact with locals and experience life in Iceland. Not just travel. The deal: work for free for 5-6 hours in exchange for a place to sleep and meals.

Located a few kilometers from Búðardalur, on the west coast of Iceland, the farm is situated in the quiet little valley of Haukadalur, where runs a river rich in salmon. An old traditional thatched shack faces the farm on the other side of the valley. This is where Erik the Red, Norwegian explorer and first European to discover Greenland put his luggage in Iceland. Called Eiríksstaðir, the building was the birthplace of Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red and first European to discover, before Columbus, the American continent. The place is today a museum. A large lake occupies the entrance to the valley and then disappears to make way for pasture. A dozen small farms dot the premises and some sheep still enjoy their freedom before the arrival of winter. Do the current locals still have in their veins the same desire for exploration that drove the Erik father and son to travel the world?

A small plantation of alaskan poplars yellowed gently around the farm. The grass is yellow-orange and the wild blueberry plants bright red. It is full autumn. I contemplate the hospitable landscape valley. Compared to many other places in Iceland, Haukadalur seems to be a small peaceful paradise where the rhythm of life through the passage of the seasons and the breeding of animals flows quietly.

Sanni has been here for nine winters. She is Finnish, passionate about breeding and milking and shares her life between Iceland and Finland. She has been employed almost permanently on the farm for nine years and she is the one who deals mainly with animals. She named all the cows, bulls and calves, about seventy heads and devote her life to maintain the production and welfare of the animals. It is a huge job for one person. The farmer, the owner, is a 60-year-old Icelandic man, recently divorced, with a strange and rough character. He is not in great shape mentally and physically and his divorce seems to have greatly affected him, although he refuses to admit it. He can not communicate otherwise than under an accusative tone and spends his time dispensing nonsensical lessons. A strange atmosphere hangs in the house where I live with the farmer, Sanni and Anneli, another volunteer from Estonia, which is not exactly what I had hoped for my last weeks in Iceland. After some very strange, disrespectful and uninteresting discussions and situations with the farmer, reminding me of bad memories of my childhood, I realized that I had to accept the exchange with the Icelanders I was looking for was not going to happen. And it was better to limit my interactions with the character so as not to keep in mind a very curious image of the local people. On the Finnish and Estonian side, however, it is a great discovery and the exchange is intelligent and interesting. Despite our differences in nationality and age, I find myself greatly in the way Sanni and Anneli see life and the world.

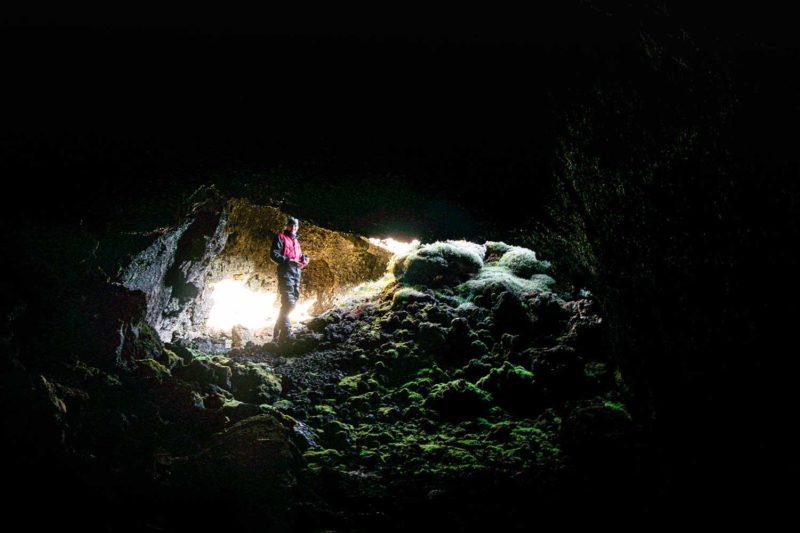

Today is fine weather and we leave, Sanni, Anneli and I, after the morning milking for a day of exploration. Sanni takes us to a small beach a few kilometers from Búðardalur. Þruma, half Icelandic dog, half Border Collie, a beautiful animal that reminds me of a wolf, plays in the water and drives away a group of wild swans. Thousands of small droplets escape from her fur as she snorts to crash into Sanni’s pants. The traditional sign of affection for all dogs. Týra the other younger dog from the farm stayed there. The farmer did not take the time to educate her and she does not know how to behave “in society”. Later, on the road to Borganes, Sanni takes us to the depths of the ground to discover a cave-tunnel. In the middle of a lava field covered with moss and dwarf birches is the entrance to a natural cave marked only by a small post. Tourists on the other side of the road hurry around the small crater of Grábrók. Nobody on our side. The place has so far still escaped the list of tourist attractions in the area. Only a few enthusiasts and connoisseurs explore it looking for entries to the many cellars dotting the lava field on which we walk.

Work clothes, gloves and flashlight and we sink in the darkness. In the light of my lamp, I can see the contours bristling with the lava blocks around us. Centuries ago, as the still-liquid lava flow covered the landscape, a bubble of air was trapped inside, forming the surprising underground passage in which we walk for almost a kilometer. Some places are several meters high. Others just a few centimeters. We must crawl carefully to avoid tearing our clothes. I feel like I am in a cocoon, in the dark, in a calm and peaceful atmosphere. There is nothing here, no animals, no life. The only danger is the risk that the tunnel collapses. But it has been here for years, so it is going to hold on a little longer, right? I think of the outlaw Icelanders, centuries ago who found refuge in places like this. Sanni could spend hours inside it seems but the light comes back slowly and we reach the end of the tunnel. We emerge in the open air among heather and birch trees.

From the top of Grábrók, the 3000 year old crater in front of the lava field, the view is splendid on the valley of Borganes. The yellow birches illuminate the landscape and I observe the small university of Bifröst spreading below. Here, in the middle of nothing, is located a university of Law, Commerce and Economy. Science and Environment would have seemed more appropriate for a place surrounded by lava fields but it is like that. For the moment, there does not seem to be a lot of people. Have classes resumed? Another day of warm weather, Sanni takes us for a walk in the valley stretching behind the farm. The soil is covered with yellow grass and small waterfalls flow along the stream. A small canyon sinks into the bottom of the valley, kilometers after the farm. The last wild berries still edible end up in our stomachs and the flow of water flowing from a waterfall hypnotizes our eyes. The two dogs run and have fun around us. I feel so good here, in this nice place. Is it still Iceland? Where are the inhospitable environments crossed on bicycle?

The days are quietly punctuated by milking, cleaning stables and outings. I know how to start the milking machine and the milk tank and even manage the milking of cows almost without problem. “You could work in a farm, if you wanted to,” Sanni told me. “You’re good at it.” The idea floats a moment in my mind and fits in the corner of the possibilities for the future. Cows of all colors scroll quietly, spilling between 5 to 10 liters of milk to the milking machine. They all have udders of different shapes and drawing milk by hand is more or less easy. In any case for Anneli and me. Sanni does it with disconcerting ease. It is important to clean the udders to remove dirt and draw some milk by hand, before putting the milker, to check that the milk does not contain bacteria. Once the milking is finished, it is necessary to clean the installation with water then to feed the newborns. Two were born during my stay. Two small calves with reddish fur. In the space of a few hours they learned to use their legs alone, to bottle feed and to do small bellowings. Nothing compare to the human baby unable to do much for years. Newborns receive the remaining milk from the machine via baby bottles and buckets where dummies have been installed. The young calves, heifers and bulls receive their portion of hay and it is finished for the morning or evening session. In between, we clean the stables of manure that accumulates, browse the meadows around the farm to gather the last animals still outside and attend a session of hooves pedicure.

This is the third time I have worked on a dairy farm. The first time was in Japan, volunteering. I came across a very small farm of about twenty old cows. The milking was done by hand by the old owner. And the volunteers only took care of cleaning the stables and feeding the animals. The second time was in New Zealand, on a farm of more than 200 animals. I worked there for a month and the cows were young heifers that were not very pleasant to milk. This third time in Iceland seems to be the right one, with relatively calm and not too many animals, a rewarding experience and an exciting exchange with Sanni and Anneli. The only thing would have be to get rid of the farmer and my two weeks here would have been perfect.

A green net slides in the sky above me. It changes shape moving like a snake in the black space tinged with stars. I am fascinated, eyes wide open. An aurora borealis. My first one. It is early October and it is still early in the season to see it. But tonight, the sky is clear and the conditions are perfect. After the evening milking that ended around 9:30pm, there was a little something in the sky. Like a ghost of a future possibility. I came out an hour later and the sky was alive. Auroras parading in the dark space. With Anneli we watched them pass for an hour. It was freezing cold but the sight of aurora changing forms, appearing, disappearing, so close and so far at the same time, made me forget the bite of the air. I tried to engrave the phenomenon in my mind, hoping to see more during the next week. My last week in Iceland.