Located along the Mediterranean Sea, Camargue, a large wetland formed by the Rhone delta, hosts a large number of plant and animal species. One of the most represented birds is a large wader with pink feathers. The Greater Flamingo. The presence of the wading bird in Camargue dates back to Roman times. According to the testimony of Pliny the Elder, the tongue of the bird was at the time a particularly sought-after dish. Today, it is its very aesthetic appearance that attracts visitors. The Greater Flamingos, whose scientific name is Phoenicopterus Roseus, belong to a family of great waders close to the Grebes family. They like lagoons and marshes and gather in large colonies that can exceed ten thousand birds during nesting. There are several subspecies but only the “Greater Flamingo” species is predominantly present in the Camargue.

Its pink color, its large size and the particular shape of its beak make the Flamingo a special wading bird. Thanks to the curved shape of its beak and the presence of fine strips of keratin between its mandibles, it can filter mud and water to only eat the small prey that interests it. Its twitter resembles that of ducks and geese. Greater Flamingos feed on crustaceans, molluscs, worms, aquatic larvae and seeds of aquatic plants. The presence of rice fields in Camargue also leads to the consumption of rice seeds by the birds during the sowing period. Watching them feed on the ponds, I have seen the head of the birds reappear in the open air covered with a mixture of water and mud giving them a strange monstrous look.

The large thin legs of the Flamingo, whose knee joint is inverted compared to that of humans, allow it to feed in deep water. They end with webbed feet so that it can move easily in the water and not sink into the mud. As for many waders, the Flamingo is accustomed to standing on one leg, whether while feeding or resting. This position does not require any energy expenditure. Due to the small size of their prey, Flamingos spend most of their time feeding. Head submerged, they trample the ground by quickly folding their long legs while turning their bodies around their beak. The movement may seem comical to the outside observer but it allows them to dig the ground (sand, mud) in order to uncover the small invertebrates that live there.

It is quite difficult to distinguish males from females in Greater Flamingos groups. Unlike many bird species, ladies possess exactly the same plumage and perform almost the same ritual movements during courtship displays. Only size makes it possible to distinguish them, females being a little smaller than males.

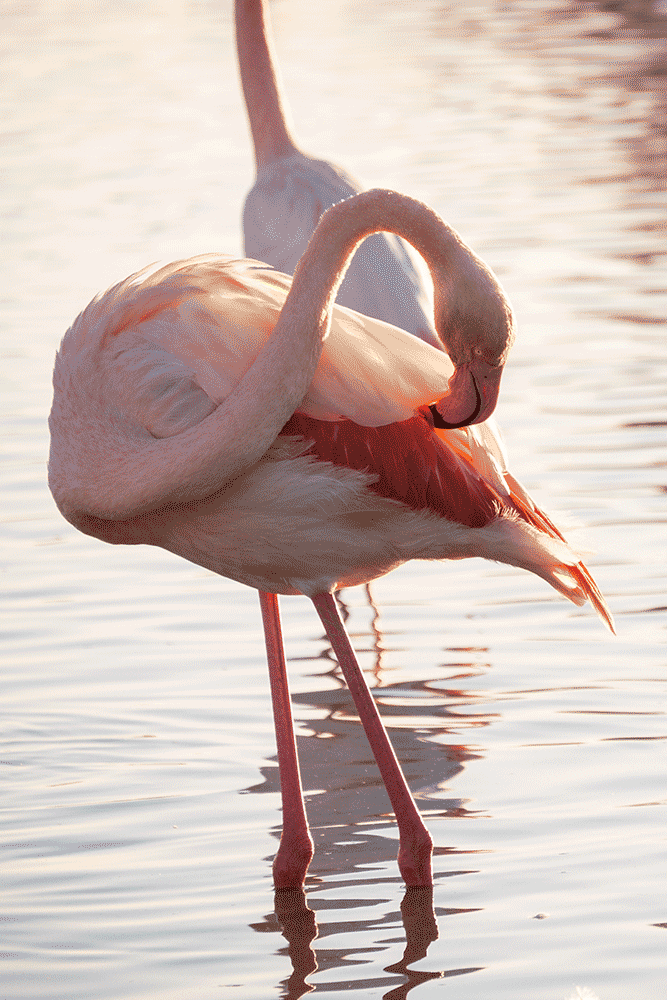

The extraordinary neck skeleton composition of the Greater Flamingo, composed of seventeen elongated cervicals, allows it to position its head in all directions. When resting, the bird uses the flexibility of its neck to rest its head on the back of its body, beak hidden in feathers. It takes three years, age of sexual maturity, for the bird to get its pink color. Juveniles are white and gray. The coloration of the legs, beak and feathers comes from the synthesis of carotenoid pigments present in their diet especially in a tiny crustacean called Artemia salina abundant in brackish water. It is this pink color that gave the bird its name. The scientific name of the Flamingo family gathering all the subspecies, Pheonicopteridae, means “blood red-feathered”, inspired by the legend of the Phoenix, with its red and gold plumage. The name “flamingo” seems to comes from “flamengo” in Portuguese or Spanish meaning “flame-colored”.

Colonies of Greater flamingos.

The color of the Flamingos varies according to seasons. Almost white in summer, they become very pink almost red in the winter during the courtship. During this period, they use an impermeable carotenoid-based oil secreted by their uropygial gland, to protect their feathers from the cold, to perk them and attract a partner.

The courtship display in Camargue starts at the end of November and brings together males and females in groups of about twenty individuals, performing a synchronized sequence of ritual postures. The first part of the dance seems to focus, as far as I could observe, on a circle movement of the group. With each individual making rapid movements of the head, from right to left, neck erect vertically, stretching to the sky. The group then start walking in a very fast and rhythmic way. The second part, shorter than the previous one, highlights the beauty of the plumage, males pushing low tones and spreading their wings vertically for a short moment, before bowing forward and deploying their wings again, this time horizontally. Females bow several time, accompanied by loud chuckles. The conclusion of the sequence seems to be reached when the general clamor diminishes. The ritual then starts again from the beginning. Once the pair is formed, the two individuals move away from the group performing the display and stay together. Flamingos seem to be of a rather quiet nature. I have, however, seen birds peck, push each other with their chest and even show attitudes of domination over their peers. Probably rivalries between males due to the search for partners.

Reproduction is done in Spring. Males climb a bit awkwardly on females to fertilize them. Following this, birds settle on small quiet islets where they build their nests, sort of mud turrets about forty centimeters high. A single egg will be laid and incubated by both parents in perfect coordination for 29 days. It will then take ten days for the little chick to be able to walk and join the nurseries where the young ones regroup. Breeding is a critical period for birds, very sensitive to any disturbance and climatic conditions. Greater Flamingos being able to live up to more than thirty years, they prefer to abstain from breeding if the conditions are not optimal. The success of the reproduction of the species in Camargue has varied greatly during history. The presence of islets is essential for nesting. Until the middle of the 20th century, variations in the course of the Rhone in the deltaic plain allowed the creation of small islets in a natural way, through a process of sedimentation and erosion. But the creation of dikes to protect Camargue and allow agriculture then led to the disappearance of islets. In the 60s, the population of Greater Flamingos declined dramatically before resume in the 70s through the creation and management of artificial islands in the Fangassier pond. There are now about ten regular breeding sites listed in the Mediterranean coastline, the Fangassier pond being one of then.

The pink wading bird is normally a migratory bird. He follows the rains at any time of the year to take advantage of the appearance of water in ponds serving as feeding and breeding sites. Going from the Mediterranean coast to Africa, through the Middle East and Southeast Asia. But it happens that certain populations, like those living in Camargue, decide to stay all year in the same place. With their large wings, whose wingspan can reach 1.8 meters, they can reach a flight speed of 70 km/h during good winds. In Camargue, it is common to see small groups of birds flying in the sky moving from ponds to ponds. The Greater Flamingo banding in Camargue began in 1947. Each year since, about 1000 chicks are captured, measured and banded before being released. The installation of plastic rings engraved with an alphanumeric code allows the accumulation of knowledge about the bird and the monitoring of the populations living in Camargue.

Protected species nationally and internationally, the Flamingo is often threatened by urban, industrial, agricultural projects and climate change. In Camargue, the Flamingo presence poses a particular problem during the flooding of rice fields in spring. Birds having become accustomed to go feed on rice seeds causing big conflicts with the rice farmers. In addition, excessive management of artificial islands for nesting may destroy the birds’ innate ability to disperse. In the presence of the same nesting site in good condition every year, birds do not go out looking for other favorable places. This instinct of adaptation is particularly important to maintain for the birds so that they can cope with the consequences of global warming. The management of the protection of the Camargue Nature Reserve and the Greater Flamingos living here raises a whole lot of questions about the coexistence of nature, animal species, tourism, industry and agriculture. And not only in Camargue but all around the Mediterranean basin. Fortunately for him, the Flamingo has beautiful aesthetic assets to maintain the mobilization in its favor. Wild species studied, tourist attraction, emblem of Camargue and photographic subject, the bird attracts a multitude of actors. Me too I let myself be seduced by its charms. And beyond the attraction it gets, the presence of the Flamingo in Camargue allows the conservation of the natural wetlands of the delta and its particular biotope.

During courtship displays, birds have a particularly colorful plumage varying from pink to red.